Digoxin vs Alternatives Decision Tool

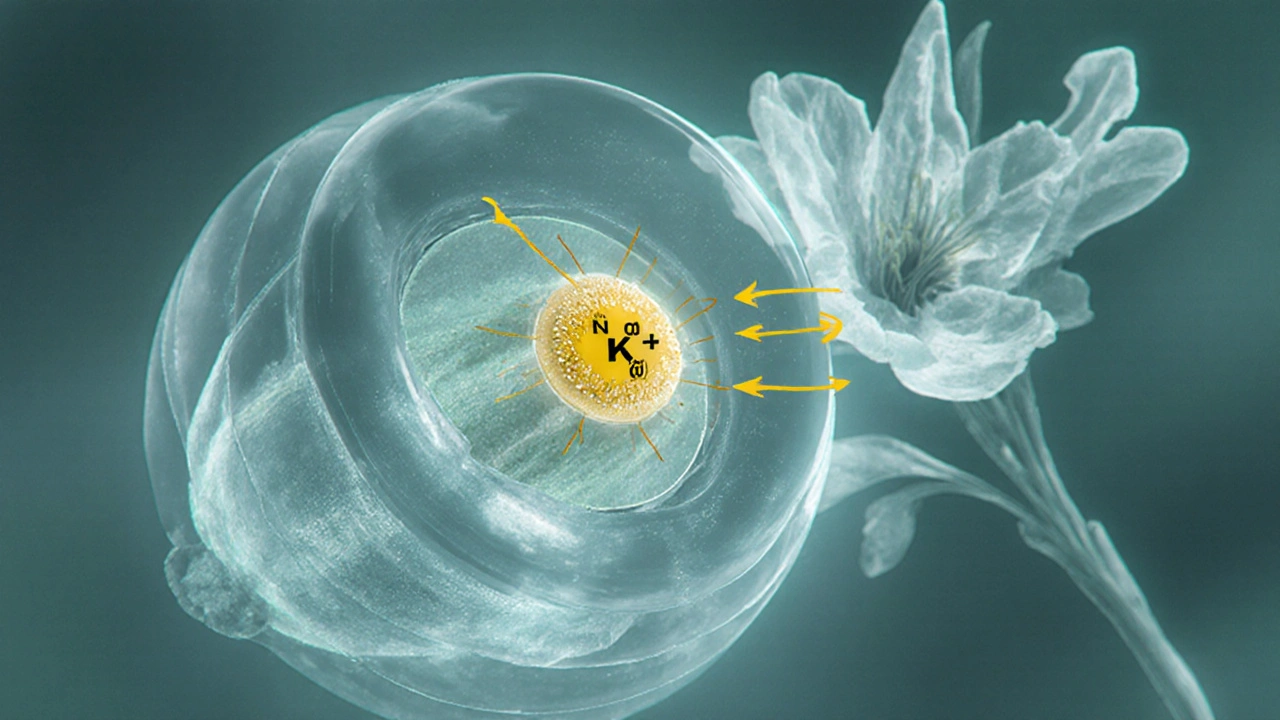

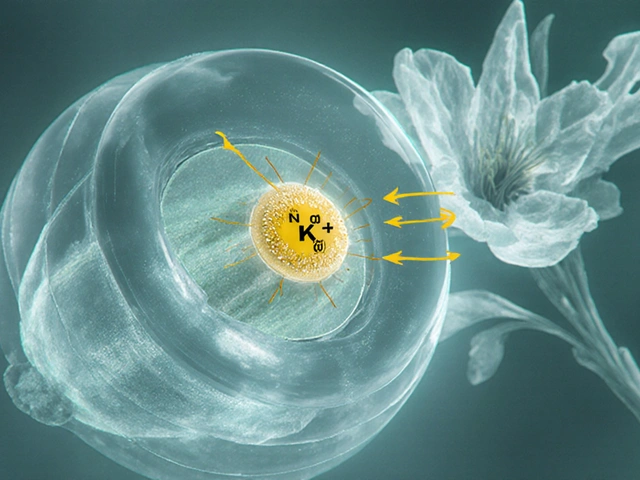

When treating certain heart conditions, Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside extracted from the foxglove plant that boosts the force of heart muscle contraction and slows electrical conduction. It’s been a staple for atrial fibrillation and systolic heart failure for decades, yet newer drug classes have entered the scene. If you’re weighing digoxin against other options, you’ll want to compare efficacy, safety, dosing convenience, and monitoring requirements.

Key Takeaways

- Digoxin works by inhibiting the Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase pump, improving contractility while controlling heart rate.

- Modern alternatives such as beta‑blockers, ACE inhibitors, and calcium‑channel blockers often have fewer toxicity concerns.

- Choosing the right drug depends on the patient’s rhythm disorder, kidney function, and risk of drug interactions.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring is essential for digoxin but not usually required for most alternatives.

- Combining agents can be effective but demands careful dose adjustments.

How Digoxin Works

Digoxin binds to the extracellular side of the Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase pump in cardiac myocytes. By partially inhibiting this pump, intracellular sodium rises, which in turn reduces the activity of the Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger. The net result is more calcium stored in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to stronger myocardial contractions (positive inotropy). Simultaneously, digoxin stimulates vagal tone, slowing conduction through the atrioventricular (AV) node, which helps control ventricular rate in atrial fibrillation.

When Digoxin Is Typically Prescribed

- Chronic systolic heart failure (ejection fraction≤35%).

- Atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, especially when beta‑blockers or calcium‑channel blockers are contraindicated.

- Patients who need a medication that can be taken once daily and have stable renal function.

Common Alternatives and Their Core Attributes

Below are the most frequently considered substitutes, each with a brief definition and key properties.

Atenolol is a cardioselective beta‑blocker that reduces heart rate, contractility, and renin release. It’s favored for hypertension, heart failure, and rate control in atrial fibrillation.

Amiodarone is a classIII anti‑arrhythmic that prolongs repolarization and blocks multiple ion channels. It’s used for resistant atrial and ventricular arrhythmias.

Lisinopril is an ACE inhibitor that dilates blood vessels by blocking the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. It improves survival in heart failure and lowers blood pressure.

Diltiazem is a nondihydropyridine calcium‑channel blocker that slows AV‑node conduction and relaxes vascular smooth muscle. It’s effective for rate control in atrial fibrillation and for angina.

Furosemide is a loop diuretic that inhibits sodium‑potassium‑chloride reabsorption in the ascending limb of the loop of Henle. It reduces preload and is a cornerstone of fluid management in heart failure.

Atrial fibrillation is an irregular, often rapid heart rhythm originating from chaotic electrical activity in the atria. Controlling ventricular rate and preventing thromboembolism are primary treatment goals.

Decision Criteria: How to Compare Drugs

When you line up digoxin next to its alternatives, consider these five factors.

- Efficacy for target condition: Does the drug reliably improve ejection fraction or achieve rate control?

- Safety profile: Frequency of serious adverse events such as bradycardia, hypotension, or organ toxicity.

- Dosing simplicity: Once‑daily versus multiple daily doses, need for titration.

- Monitoring burden: Requirement for serum levels, ECG, kidney function checks.

- Drug‑interaction risk: Especially with other cardiac meds, antibiotics, or anti‑arrhythmics.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Drug | Mechanism | Primary Indication | Typical Dose | Major Side Effects | Monitoring Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin | Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase inhibition → ↑ intracellular Ca²⁺ | Heart failure, atrial fibrillation | 0.125‑0.25mg PO daily (adjust for kidney) | Arrhythmia, nausea, visual disturbances | Serum level, renal function, electrolytes |

| Atenolol | Beta‑1 receptor blockade | Hypertension, heart failure, AF rate control | 25‑100mg PO daily | Bradycardia, fatigue, bronchospasm | Pulse, blood pressure; no serum level |

| Amiodarone | Multi‑channel block (K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺) & β‑blockade | Refractory atrial/ventricular arrhythmias | 200‑400mg PO daily (loading), then 100‑200mg | Pulmonary fibrosis, thyroid dysfunction, liver injury | Liver enzymes, thyroid tests, chest X‑ray |

| Lisinopril | ACE inhibition → ↓ angiotensinII | Heart failure, hypertension | 5‑20mg PO daily | Cough, hyperkalemia, angioedema | Renal function, potassium |

| Diltiazem | Calcium‑channel blockade (AV‑node) | AF rate control, angina | 120‑360mg PO daily (extended‑release) | Constipation, edema, AV block | ECG, blood pressure |

| Furosemide | Loop diuretic - Na⁺/K⁺/Cl⁻ reabsorption inhibition | Fluid overload in heart failure | 20‑80mg PO daily (adjustable) | Electrolyte loss, ototoxicity, dehydration | Electrolytes, renal function |

Choosing the Right Agent for a Given Patient

Imagine you have three typical scenarios.

- ScenarioA: A 68‑year‑old with HFrEF (EF30%) and chronic kidney disease (eGFR45mL/min). Digoxin’s narrow therapeutic window makes dosing tricky, while an ACE inhibitor like lisinopril offers proven mortality benefit with easier monitoring.

- ScenarioB: A 55‑year‑old with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation who experiences bronchospasm with non‑selective beta‑blockers. Diltiazem provides rate control without lung side effects, but if the patient also has peripheral vascular disease, the vasodilatory effect may be desirable.

- ScenarioC: A 72‑year‑old with longstanding AF, low blood pressure, and a history of thyroid disease. Amiodarone can achieve rhythm control when other drugs fail, yet its thyroid toxicity risk demands regular TSH checks-something the patient may struggle with.

In each case, weighing the five decision criteria helps narrow the choice. A practical rule of thumb: start with agents that have the simplest monitoring (beta‑blockers, ACE inhibitors, calcium‑channel blockers) unless digoxin’s inotropic effect is essential.

Practical Tips for Safe Digoxin Use

- Check renal function before initiating therapy; reduce dose if eGFR<60mL/min.

- Correct serum potassium and magnesium; low levels heighten arrhythmia risk.

- Obtain a baseline ECG; look for PR‑interval prolongation.

- Schedule serum digoxin level 6‑8hours after the third dose; target 0.5‑2ng/mL for most patients.

- Educate patients to report visual changes (yellow‑green halos) or persistent nausea.

Potential Pitfalls When Switching From Digoxin to an Alternative

- Never stop digoxin abruptly in a patient with severe systolic dysfunction; taper over 1‑2weeks while initiating the new agent.

- Avoid overlapping AV‑node blockers (e.g., beta‑blocker + diltiazem) unless you closely monitor heart rate and PR interval.

- Be aware of drug-drug interactions: macrolide antibiotics, quinidine, and some antifungals can raise digoxin levels dramatically.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is digoxin still recommended for heart failure in 2025?

Guidelines now place digoxin as a second‑line option after ACE inhibitors, beta‑blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. It is useful when patients remain symptomatic and have a low resting heart rate, but careful monitoring is mandatory.

Can I take digoxin together with a beta‑blocker?

Yes, the combination is common for rate control in atrial fibrillation. The key is to watch for excessive bradycardia and adjust doses accordingly.

What are the signs of digoxin toxicity?

Early signs include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and visual disturbances (yellow‑green halos). Cardiac manifestations range from premature beats to high‑grade AV block. Prompt serum level testing is essential.

How does atenolol compare to digoxin for rate control?

Atenolol slows heart rate by blocking sympathetic stimulation, which rarely causes visual disturbances and doesn’t need serum level checks. However, it can worsen asthma and may be less effective in patients with high catecholamine states. Digoxin directly affects AV‑node conduction and can be useful when beta‑blockers are contraindicated.

Is routine ECG monitoring required for patients on diltiazem?

Baseline ECG is recommended, then periodic checks if the dose exceeds 240mg/day or if the patient develops symptoms of bradycardia. Unlike digoxin, there is no need for serum concentration testing.

Alright folks, digoxin is the old‑school heart drug that still thinks it runs the show. If you’re still handing it out like candy, you’re basically saying “let’s live in the 1800s” while pretending you care about modern pharmacology. Your patients deserve better than a relic that pushes you into arrhythmias just for kicks.

The decision tool you posted is solid, but remember that renal clearance is a key factor – digoxin’s half‑life balloons when eGFR drops below 30 mL/min. Alternatives like amiodarone or beta‑blockers have more predictable pharmacokinetics in kidney impairment, and they avoid the narrow therapeutic index that makes digoxin dosing a minefield. Also, keep an eye on drug‑drug interactions; many anti‑arrhythmics inhibit P‑glycoprotein, raising digoxin levels unexpectedly.

People love to brand digoxin as “the villain” while ignoring that every drug has a shadow side. If we strip away the hype, what we’re really confronting is our own fear of uncertainty – we’d rather cling to a known risk than dive into the unknown world of newer agents that lack decades of post‑marketing data. In the end, it’s less about the molecule and more about the comfort of familiarity.

i get it you want to keep the conversation friendly but digoxin does have a very narrow therapeutic index and that is why monitoring is essential

digoxin can be useful but only if you respect its power it is not a toy for quick fixes

From a cultural and clinical perspective, it is essential to appreciate that therapeutic choices often reflect regional practice patterns and patient preferences. While digoxin remains a cornerstone in the management of certain congestive heart failure phenotypes, the emergence of sacubitril/valsartan and ivabradine offers clinicians alternative pathways that may align more closely with contemporary guideline recommendations. It is therefore prudent to evaluate each patient’s comorbid burden, renal function, and quality‑of‑life goals before defaulting to any single agent.

i cant believe people still havve the audacity to prescribe digoxin without a full risk assessment it is like handing out knives to kids i tought medicine was about dooing no harm but this is just plain irresponsible

It’s great you’re looking at the tool – take the time to match the drug to the patient’s overall picture. A balanced approach will help you feel confident in the choice.

Let me lay it out straight: digoxin is the dinosaur in a world of sleek, gene‑targeted therapies, and yet it stubbornly clings to the spotlight.

You think you’re being avant‑garde by pulling up a flashy comparison widget, but you’re just repackaging the same old debate.

First, the pharmacodynamics – a narrow therapeutic index that makes dosing feel like Russian roulette, especially when you factor in electrolyte shifts.

Second, the pharmacokinetics – renal clearance that can double your plasma concentration overnight if the kidneys decide to take a vacation.

Third, the drug‑drug interactions – P‑gp inhibitors, macrolides, amiodarone, they all conspire to turn a modest dose into a lethal cocktail.

Now, consider the alternatives: beta‑blockers, ACE inhibitors, ARNIs – each with their own side‑effect profiles, but none of them demand hourly serum level checks.

Sure, beta‑blockers can cause bradycardia, but at least they don’t make you chase a blood level on a Saturday morning.

And ARNIs, while pricey, have been shown in large trials to reduce mortality without the nail‑biting monitoring regimen.

If you’re still insistent on digoxin, you must implement strict criteria: ejection fraction under 30%, persistent atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, and no better tolerated options.

Even then, you need to educate the patient about visual disturbances, GI upset, and the dreaded yellow‑green halos that signal toxicity.

Do not forget that digoxin’s efficacy in modern heart failure is modest at best, offering only a slight improvement in symptoms without a mortality benefit.

Meanwhile, newer agents are chipping away at its relevance faster than you can type ‘digoxin’ into a Google search.

In my experience, clinicians who cling to digoxin are often either entrenched in old training paradigms or simply lazy to stay current.

So before you click ‘compare’, ask yourself whether you’re comparing a relic to a revolution or just polishing a tired trophy.

The answer, dear reader, is that unless you have a compelling, guideline‑endorsed indication, digoxin belongs in the museum, not on the bedside cabinet.

Choose wisely, because the patients will thank you when you spare them the hassle of frequent labs and unpredictable side effects.

digoxin may still have a niche but it’s rarely the first line

Another outdated drug? 🙄