When a biologic drug hits the market, it doesn’t just come with a price tag-it comes with a legal shield. In the U.S., that shield lasts 12 years. During that time, no biosimilar can be approved, no matter how similar it is or how much cheaper it could be. This isn’t just a technicality. It’s a system designed to protect innovation, but one that also delays affordable alternatives for millions of patients.

What Exactly Is a Biologic, and Why Does It Matter?

Biologics are medicines made from living organisms-cells, proteins, or tissues. Think of them as complex, living drugs. Insulin, Humira, Enbrel, and cancer treatments like Herceptin are all biologics. Unlike traditional pills (generics), which are chemically synthesized and easy to copy, biologics are made in living cells. Even tiny changes in the manufacturing process can alter how they work. That’s why you can’t just make a direct copy. You have to make a biosimilar. The FDA defines a biosimilar as a product that is “highly similar” to an approved biologic, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. That sounds straightforward. But getting there? It’s anything but.The 12-Year Clock: How the BPCIA Controls Entry

The rules for biosimilar entry are set by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009. It’s not just one rule-it’s two layers of protection. First, there’s a 4-year data exclusivity period. During this time, a biosimilar company can’t even submit an application to the FDA. They can’t start the process. They have to wait. Then comes the 12-year market exclusivity. Even after those four years, the FDA still can’t approve a biosimilar until 12 years after the original drug was approved. That’s a full decade and a half of protection before competition can legally begin. This isn’t arbitrary. The law was written to balance two goals: reward companies for investing in expensive, risky biologic research, and eventually let cheaper versions enter the market. But in practice, the 12-year window often feels like a lock.Patent Thickets: The Hidden Delay Tactic

The BPCIA also created something called the “patent dance.” It sounds like a formal procedure, but it’s become a legal battleground. Here’s how it works: When a biosimilar company applies to the FDA, they must share their application with the original drug maker. The original company then lists every patent they think might be violated-sometimes dozens. Then the biosimilar company responds, saying which patents they believe are invalid or don’t apply. Then both sides negotiate which patents to fight over. It’s supposed to be a way to avoid endless lawsuits. But it rarely works that way. Take Humira. Its main patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie, the maker, held over 160 patents on the drug. They used those to file lawsuits against every biosimilar company that tried to enter. Each lawsuit delayed approval by months, sometimes years. By the time the first Humira biosimilar got FDA approval in 2023, it was seven years after Europe had already started selling cheaper versions. This isn’t rare. It’s standard. According to Duke University law professor Arti Rai, 87% of biosimilar legal cases involve multiple patent claims. These aren’t just about protecting real innovation-they’re about stretching out monopolies.

Why the U.S. Lags Behind the World

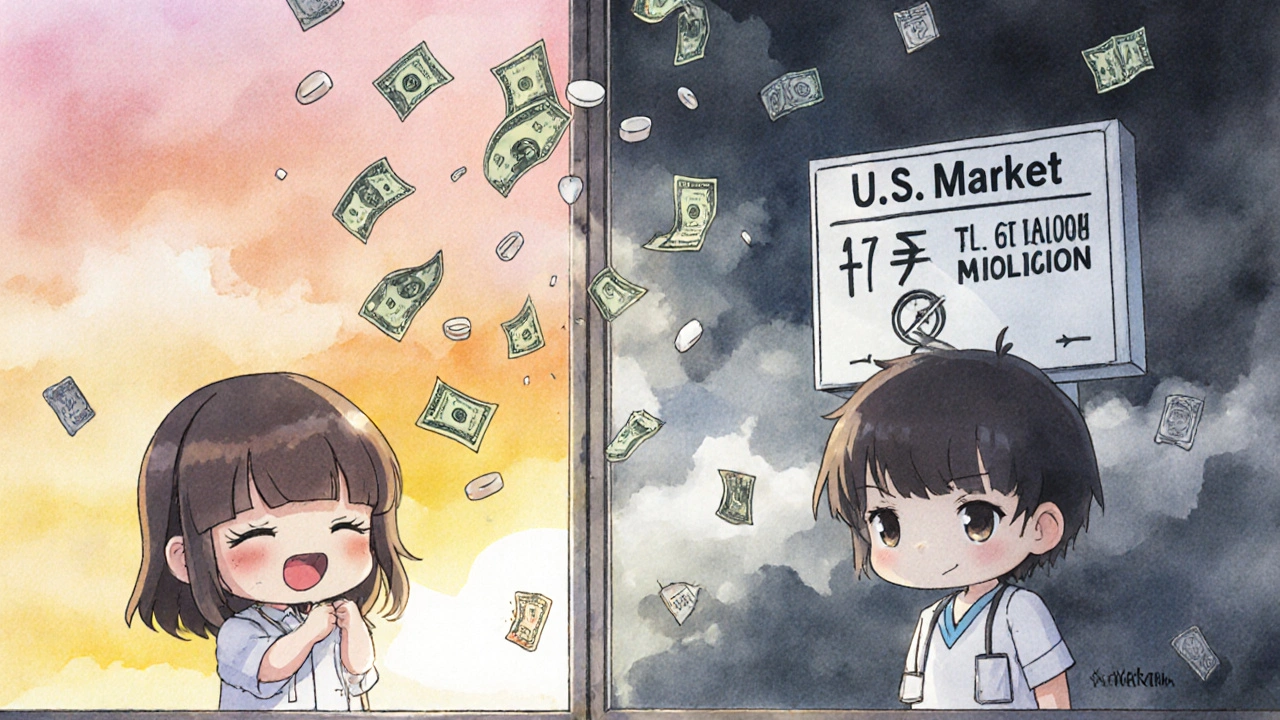

The U.S. isn’t the only country with biologic protections. But it has the longest. - The European Union gives 10 years of data exclusivity, plus 1 year of market exclusivity-11 total. - Japan offers 8 years of data exclusivity and 4 years of market exclusivity-also 12, but with different timing. - South Korea gives 10 years of data exclusivity and no extra market protection. The result? Patients in Europe got access to biosimilars for Humira in 2018. In the U.S.? Not until 2023. That five-year gap cost American patients an estimated $167 billion in extra spending on biologics, according to I-MAK. And it’s not just Humira. Enbrel, Eylea, and others followed the same pattern. By the time biosimilars finally entered the U.S., prices had skyrocketed. Meanwhile, in Europe, prices dropped 30-70% after biosimilars arrived.The Cost of Waiting: Real People, Real Pain

Behind every delay is a patient who can’t afford treatment. Dr. Peter Bach from Memorial Sloan Kettering found that U.S. patients pay up to 300% more than Europeans for the same biologic drugs. A patient on Humira in the U.S. might pay $7,000 a month. In Germany? Around $2,000 after biosimilars entered. The National Community Pharmacists Association surveyed pharmacists in 2022. 63% said they’d had patients stop taking their biologic because they couldn’t afford it. 78% believed the current patent system unnecessarily delays access. For someone with rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, or cancer, waiting five extra years for a cheaper option isn’t just inconvenient-it’s dangerous. Many patients delay treatment, skip doses, or drop out entirely.

Okay but let’s be real-why are we still acting like Big Pharma is the hero here? I’ve got a friend on Humira who pays $6k/month out of pocket. She works two jobs and still skips doses. Meanwhile, the CEO of AbbVie just bought a private island. This isn’t innovation-it’s extortion dressed up in lab coats.

And don’t give me that ‘but they need to recoup R&D!’ nonsense. They spent $2B on marketing last year. That’s more than they spent on R&D for Humira in the last decade. The math doesn’t add up. It never does.

We’re not asking for free drugs. We’re asking for the same access Europeans have. Five years. That’s all it took for them to slash prices. Five years we lost. Five years of people dying because they couldn’t afford to live.

I’m not mad. I’m just… done.

uuhhh… i think u r wrong?? like… maybe the 12 years is needed?? like… what if they just… like… make a drug and then someone copies it and it kills people?? like… not all biosimilars are safe?? idk??

...I find it interesting that the FDA approves biosimilars... but only after... a decade... and after... multiple lawsuits... and yet... the same agency... approves new drugs... in under a year... for rare cancers... with less data...

It’s... inconsistent...

And... the patent dance... it’s... not a dance... it’s... a trap...

...I think... someone... should... write a letter... to Congress...

...but... I’m... too... tired...

...maybe... tomorrow...

The data is unequivocal: 12-year exclusivity is an economic distortion masquerading as innovation policy. The marginal cost of manufacturing biosimilars is 15-20% of the original biologic. The R&D amortization argument collapses under scrutiny when 87% of patent litigation involves non-core claims. The Congressional Budget Office’s $158B savings projection is conservative. The real cost is measured in lives deferred, not ledger entries. The FDA’s 38 approvals in 10 years versus the EU’s 88 is not a regulatory difference-it’s a moral failure.

And yet, we continue to subsidize this rent-seeking behavior through Medicare Part B reimbursement structures. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a FDA stamp.

I just want to say thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse and I see this every day. Patients crying because they can’t afford their meds. Families choosing between rent and insulin. It’s not fair.

And honestly? I don’t think most people even know how long this has been going on. I’ve shown this article to three patients this week. All of them were shocked. We need more people to see this.

It’s not that we don’t have the science. We do. We have the will. We just don’t have the political courage.

Let’s change that. Together.

They’re lying. The 12 years is a cover. The real reason is the shadow government controls the FDA. The same people who own the drug companies own the regulators. They’re using patents to control the population. You think this is about money? It’s about control. Watch what happens when the next big drug expires. Nothing will change. They’ll just make a new law.

How can anyone with a conscience defend this? This isn’t capitalism. It’s corporate feudalism. And you, the American public, are the serfs. You pay for the drugs, you pay for the research, you pay for the lobbying, and then you beg for scraps while the pharmaceutical barons sip champagne in their penthouses.

Europeans have had common sense for years. Americans still think ‘free market’ means ‘let the rich steal everything.’

Shameful. Utterly shameful.

Let me tell you something. I’ve seen this play out in the trenches. Biosimilar companies? They’re not the heroes you think they are. They’re hedge funds with PhDs. They wait until the patent clock’s about to run out, then they swoop in like vultures. They don’t care about patients. They care about margins. They’ll undercut the original drug by 80%, then jack up prices after the original maker pulls out. It’s not altruism. It’s arbitrage.

And don’t get me started on the FDA’s ‘fast track.’ It’s a joke. They approve biosimilars that are ‘highly similar’-but what does that even mean? You can’t replicate a living molecule. You’re playing with fire.

So yes, the system’s broken. But the solution isn’t ‘more biosimilars.’ It’s better regulation. And fewer people pretending to be saints.

There’s a nuance here that’s being lost in the outrage. The 12-year exclusivity period wasn’t handed to Big Pharma as a gift-it was negotiated after years of bipartisan debate, with input from patient advocates, scientists, and even generic drug manufacturers. The fear back then was that without strong protections, no company would ever risk the $2 billion and 10-year development timeline required to bring a biologic to market.

And yes, patent thickets are abusive. Absolutely. But dismantling the exclusivity window entirely? That’s like burning down the house to get rid of the rats. We need targeted reform: cap the number of patents that can be asserted, shorten the data exclusivity period for orphan drugs, and fund public biosimilar development for rare conditions.

It’s not ‘pharma bad, patients good.’ It’s ‘system broken, let’s fix it smartly.’

And we can. But we have to stop treating this like a morality play and start treating it like a policy problem.

As someone from India where biosimilars are widely available and affordable, I want to say this: the U.S. system is not just broken-it’s morally indefensible. In India, we have biosimilars of Humira for under $50 a month. We have patients on them for over 10 years with no safety issues. The science is proven. The manufacturing is scalable.

But here? You’re paying 100x more because of legal games and corporate greed. And the worst part? You’re told it’s ‘for your own good.’

Let me tell you something-when your child needs a biologic and you can’t afford it, no amount of ‘innovation protection’ matters. What matters is that they breathe tomorrow.

I urge you: don’t just be angry. Write to your reps. Share this. Demand change. We can’t wait for the system to fix itself. We have to fix it ourselves.

And if you think this is too complicated? Just ask yourself-would you want someone you love to wait five years for a drug that could save their life? Because that’s what’s happening every single day.

Enough is enough.

George, you’re right about the nuance. But here’s the thing-nobody’s asking to eliminate exclusivity. We’re asking to cut it to 7 years, like Canada and Australia. That’s still more than enough time to recoup R&D. And we’re asking to ban patent trolling-like the 160-patent stunt on Humira.

It’s not about killing innovation. It’s about stopping exploitation.

And honestly? If the system was truly fair, we wouldn’t need to have this conversation. Patients wouldn’t be choosing between rent and insulin. Companies wouldn’t be lobbying to extend monopolies while their CEOs take vacations on yachts.

So yes-fix it smartly. But don’t call it ‘nuance’ when the cost is human lives.

We’re not asking for the moon. We’re asking for the same deal Europe got 5 years ago.

When will we get ours?