What Exactly Is a Hip Labral Tear?

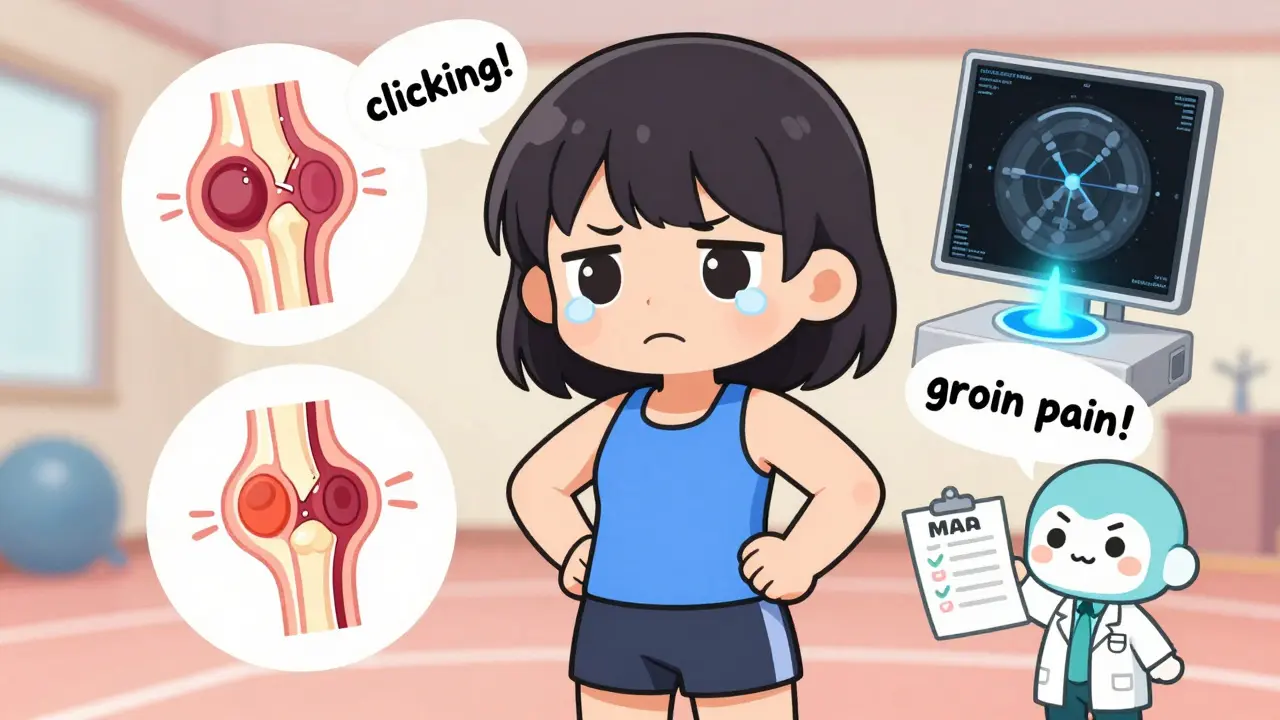

A hip labral tear happens when the ring of cartilage around the socket of your hip joint gets damaged. This cartilage, called the labrum, acts like a rubber seal-it keeps the ball of your femur snug inside the socket, stabilizes the joint, and absorbs shock. When it tears, you don’t just feel pain; you might hear clicking, locking, or feel like your hip is catching. For athletes, this isn’t just an inconvenience-it can end a season or even a career if not handled right.

Most tears aren’t from one big injury. They build up over time. Think of a soccer player twisting to kick, a basketball player cutting hard, or a dancer holding a deep turnout. These motions put extreme pressure on the hip. The most common cause? Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). That’s when the bones of the hip are shaped in a way that rub against each other during movement. Over months or years, that friction wears down the labrum like a shoe sole wearing thin from constant use.

Who’s Most at Risk?

If you’re an athlete under 40, especially in sports that demand deep hip rotation, you’re in the high-risk group. Basketball players, soccer athletes, hockey skaters, gymnasts, and distance runners make up the bulk of cases. Studies show that 22% to 55% of athletic hip pain cases involve a labral tear. In some sports, like ballet or hockey, the rate is even higher because of the extreme ranges of motion required.

It’s not just about how hard you train-it’s about your anatomy. People with hip dysplasia (a shallow socket) or FAI are far more likely to tear their labrum. In fact, untreated dysplasia leads to a 60-70% chance of re-tearing after surgery. That’s why simply repairing the labrum isn’t always enough. If the bone structure is flawed, the tear will likely come back.

How Do You Know You Have One?

There’s no single symptom that screams “labral tear.” Pain in the front of the hip or groin is common, especially when you sit for long periods, twist, or squat. Some people feel a deep ache. Others feel sharp clicks or a catching sensation. The pain often mimics a groin strain or hip pointer, which is why so many athletes delay diagnosis.

Doctors use physical tests to spot red flags. The FADIR test (flex, adduct, and internally rotate your hip) and the FABER test (flex, abduct, and externally rotate) are the two most reliable. If these movements cause sharp pain or a click, there’s a strong chance you have a tear. Studies show these tests trigger symptoms in 78% of confirmed cases.

But physical exams alone aren’t enough. You need imaging.

Imaging: Why MRA Beats Regular MRI

Plain X-rays come first. They don’t show soft tissue, but they reveal bone shape-whether you have FAI, dysplasia, or arthritis. That’s critical because treatment changes based on bone structure.

Standard MRI? It misses up to 30% of labral tears. That’s why many athletes get stuck in limbo-pain persists, MRI says “normal,” and they’re told to rest and stretch. But here’s the truth: if your pain lasts more than 6 weeks and doesn’t improve with rest, you need a better scan.

Magnetic Resonance Arthrography (MRA) is the gold standard for imaging. It involves injecting contrast dye into the hip joint before the MRI. The dye fills the space around the labrum, making even tiny tears visible. MRA detects labral tears with 90-95% accuracy, compared to 35-60% for regular MRI. The International Hip Documentation Society recommends MRA for all athletes being evaluated for labral pathology. It’s expensive-$1,200 to $1,800 out-of-pocket in many cases-but it saves time, money, and future surgeries by getting the diagnosis right the first time.

Now, newer 3D MRI sequences are emerging. A 2023 multicenter trial showed they boost accuracy to 97%, especially for partial tears. But MRA remains the most widely used and trusted method.

Conservative Treatment: Can You Avoid Surgery?

Not everyone needs surgery. For mild tears or those without major structural issues, conservative care works. The first step? Rest. Stop the sports that hurt. Avoid deep squats, pivots, and prolonged sitting. Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen to reduce inflammation.

Physical therapy is the next step-but it’s not one-size-fits-all. Some clinics report only 30-40% success with PT alone. Others, like True Sports Physical Therapy, say 65% of athletes avoid surgery with the right program. The difference? Specialized protocols. Good PT focuses on:

- Restoring hip mobility without forcing the joint

- Strengthening the glutes and core to offload pressure from the hip

- Correcting movement patterns that caused the tear

Corticosteroid injections can help too. They reduce inflammation and give you a 3-6 month window to rehab without pain. About 70-80% of patients get relief, but it’s temporary. It doesn’t heal the tear-it just makes it easier to move.

Some clinics now offer platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections. A 2022 trial at Hospital for Special Surgery found 55% of patients avoided surgery after one PRP shot. It’s not magic, but for athletes who want to delay surgery or avoid it altogether, it’s a real option.

When Surgery Becomes Necessary

If you’ve tried 3-6 months of rest, PT, and injections-and you’re still in pain or can’t return to sport-it’s time to consider arthroscopy.

Hip arthroscopy is minimally invasive. The surgeon makes two or three small incisions, inserts a camera and tiny tools, and either:

- Debrides (trims) the torn part of the labrum

- Repairs it using suture anchors to reattach it to the bone

But here’s the key point: isolated debridement is outdated. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons warns against trimming the labrum without fixing underlying bone issues like FAI or dysplasia. Why? Because without correcting the root cause, you’re just cutting away tissue that will tear again. Studies show 40% higher revision rates when bone problems are ignored.

For athletes with dysplasia, the solution is often a combined procedure: fix the bone shape (like a periacetabular osteotomy) and repair the labrum at the same time. This isn’t a simple fix-it’s a major surgery-but it cuts re-tear risk from 70% down to under 20%.

Recovery: What to Expect After Surgery

Recovery isn’t fast. It’s not even linear. But it’s predictable if you follow the plan.

After a labral repair, you’re on crutches for 2-4 weeks. No weight-bearing on the hip. Then, you start slow motion exercises. The full rehab takes 5-6 months. After a debridement, you’re back in 3-4 months.

Here’s what the rehab phases look like:

- Protection (Weeks 1-6): Focus on reducing swelling, regaining range of motion without strain. No twisting or deep hip flexion.

- Strengthening (Weeks 7-12): Start glute and core work. Use resistance bands, not weights. Quadriceps strength must reach 90% of the good leg before moving on.

- Sport-Specific Training (Weeks 13-20): Jogging, lateral movements, controlled pivots. No cutting or jumping yet.

- Return to Sport (Weeks 21-26): Only when you have full pain-free internal rotation (30 degrees), 90% strength symmetry, and no swelling after activity.

Professional athletes like NHL player Ryan Nugent-Hopkins took 5.5 months to return to play. Amateur athletes with good rehab programs often return in 4-5 months. But skip phases? You risk re-injury or chronic pain.

Success Rates and Long-Term Risks

Most athletes bounce back. Studies show 85-90% of athletes under 35 return to their pre-injury level after proper surgery. That number drops to 70-75% for those over 35. Why? Healing slows with age, and joint wear is already starting.

But here’s the real concern: untreated tears lead to osteoarthritis. A 15-year study found people with labral tears are 4.5 times more likely to develop hip OA within a decade. That’s why early, accurate diagnosis isn’t just about getting back to the field-it’s about keeping your hip healthy for life.

Complications happen, but they’re rare with experienced surgeons. Persistent pain affects 15-20% of patients. Heterotopic ossification (bone growing in soft tissue) occurs in 5-10%. Nerve injury is under 2%. Revision surgery is needed in 8-12% of cases within five years.

What Athletes Are Saying

On Reddit’s r/running community, one marathoner returned to racing at 4.5 months after repair with a strict PT plan. Another dancer needed a second surgery because the first one missed the tear. The difference? The first had access to a sports medicine specialist with MRA and a clear rehab plan. The second went to a general orthopedist who didn’t recognize the complexity.

Patients at specialized centers report 92% satisfaction. Those at general clinics? Only 75%. Why? It comes down to experience. Hip arthroscopy has a steep learning curve. Surgeons need 50-100 procedures to become proficient. That’s why athletes who travel to centers with high-volume hip programs do better.

What’s Next for Treatment?

The field is moving fast. In June 2023, the FDA approved a new bioabsorbable suture anchor-Smith & Nephew’s BioX. It dissolves over time, reducing long-term irritation. Early data shows 89% success at two years, better than traditional metal anchors.

More clinics are using ultrasound-guided injections to target not just the labrum, but nearby tendons and bursae that often contribute to pain. And as 3D MRI becomes more accessible, surgeons will be able to plan repairs with even more precision.

By 2027, experts predict 75% of labral repairs will be done entirely through arthroscopy. That means smaller cuts, faster recovery, and less scarring.

Bottom Line: Don’t Ignore Hip Pain

If you’re an athlete and your hip hurts during or after activity, don’t just “wait it out.” Labral tears don’t heal on their own. Ignoring them increases your risk of early arthritis. Get an X-ray. If pain continues, demand an MRA. See a sports medicine specialist-not just any orthopedist. And if surgery is recommended, make sure they’re addressing bone structure, not just trimming cartilage.

Recovery takes time. But with the right diagnosis and care, most athletes don’t just return to their sport-they come back stronger.

This is why American athletes are getting wrecked. We train too hard, too soon, no respect for the body. Just push through like it's 1995. My cousin tore her labrum playing college soccer and they told her to ice it. Now she's on disability. Fix the system not the hip.

Labral tears? More like labral conspiracies. I bet 80% of these diagnoses are just doctors trying to sell MRIs. I played football for 12 years with hip pain and never got one. Just gritted through it. Now I'm 40 and still running marathons. Who needs fancy scans?

It is imperative to underscore the profound clinical significance of early and accurate diagnostic intervention in the context of hip labral pathology. The data presented herein, while statistically compelling, fails to adequately address the socioeconomic disparities that prevent equitable access to MRA imaging, particularly among low-income collegiate athletes. Furthermore, the normalization of surgical intervention without comprehensive biomechanical assessment constitutes a troubling paradigm in contemporary orthopedic practice.

i had a labral tear in 2021 and did PT for 8 months and it went away but my doc said i had FAI and i was like wait what is that? then i googled it and now im scared every time i squat. also i think the guy who wrote this is a pharma shill.

Hey athlete friends, I know this is scary but you got this! I've seen so many of my clients go through this and come out stronger than ever. Don't rush the rehab. Take the time. Listen to your body. And if your PT doesn't know the difference between debridement and repair? Find a new one. You deserve better than a cookie-cutter plan. Your hip will thank you in 10 years.

The real tragedy isn't the tear-it's the cultural delusion that the body is a machine to be optimized. We've turned athletes into data points, their pain into KPIs. MRA? PRP? Arthroscopy? These are just shiny Band-Aids on a society that worships performance over presence. You don't heal a labrum by cutting it. You heal it by asking why it tore in the first place. Maybe the problem isn't your hip. Maybe it's the system that demanded you push through pain for a scholarship, a contract, a highlight reel.

MRA is a scam. The dye is laced with nanoparticles that track your movements. I read a forum where a guy said after his MRA his phone started auto-opening YouTube videos of ballet. Coincidence? I don't think so. Also the FDA approved that new suture anchor? That's from Smith & Nephew who also owns the company that makes the antidepressants your doc prescribes when you're depressed from not playing. They're all connected.

The clinical management of hip labral pathology necessitates a multidisciplinary approach that prioritizes biomechanical correction over symptomatic palliation. It is therefore imperative that practitioners adhere to evidence-based protocols, particularly in the context of concomitant femoroacetabular impingement, wherein isolated debridement constitutes a suboptimal therapeutic strategy with significantly elevated rates of revision surgery. Furthermore, patient selection for arthroscopic intervention must be guided by rigorous preoperative imaging and functional assessment.

This is why black athletes get dropped from teams. They don't have money for MRA so they get told it's just a strain. Then they can't play. Then they get kicked out. Meanwhile rich kids get the dye and the surgery and come back stronger. This isn't medicine. This is capitalism with a stethoscope.

You people are so naive. Labral tears are rare. What you're feeling is probably just your ego. You think you're special because you play sports? Newsflash: your hip doesn't care. And if you're getting surgery because you can't squat deep? Maybe you shouldn't be squatting deep. Maybe your body is telling you to stop pretending you're an athlete. You're not a pro. You're a weekend warrior with delusions of grandeur.

I used to be a dancer. I had a tear. I didn't get MRA because I didn't have insurance. I got a $200 generic MRI that said 'mild degeneration.' So I kept dancing. For three years. Until I couldn't walk. Now I'm on painkillers and my hip makes a noise like a rusty hinge. They told me I could've avoided it. But who listens to doctors when you're 21 and your body feels like a temple? Turns out temples don't come with warranties.

mra is overrated. i had a tear and just did yoga and now im fine. also why are all these studies funded by hospitals? they want you to get surgery so they can make money. i got my hip checked by a guy who fixes lawnmowers. he said my socket looked fine. i believe him more than some guy in a white coat with a 1200 dollar machine.