The Federal Circuit Court doesn’t just hear patent cases-it owns them. In the U.S., every single patent appeal, no matter where it starts, ends up in this one court. That includes the most complex, high-stakes cases in pharmaceuticals. When a drug company sues a generic maker over a patent, or when a generic company tries to knock out a patent before launching a cheaper version, it’s the Federal Circuit that makes the final call. This isn’t just another appeals court. It’s the only one that handles patent law nationwide, and that gives it enormous power over how medicines reach patients and how much they cost.

Why the Federal Circuit Controls Pharmaceutical Patents

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit was created in 1982 to fix a broken system. Before then, patent cases were scattered across 12 regional circuit courts. One court might say a drug patent was valid; another might say the same patent was obvious. Companies couldn’t predict outcomes. The solution? Centralize all patent appeals in one court. That court became the Federal Circuit.

Today, it handles every patent appeal from every district court in the country. That includes cases under the Hatch-Waxman Act, the law that balances brand-name drug innovation with generic competition. When a generic drug maker files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA, it’s essentially saying: ‘We think this drug doesn’t infringe your patent.’ The brand-name company then sues. And that lawsuit? It goes to the Federal Circuit on appeal.

No other court has this authority. The Ninth Circuit hears copyright cases. The Second Circuit handles securities fraud. But only the Federal Circuit decides what makes a pharmaceutical patent valid, enforceable, or invalid. That’s why every major drug company, generic manufacturer, and patent lawyer watches its rulings closely.

ANDA Filings Create Nationwide Jurisdiction

In 2016, the Federal Circuit changed the game with its ruling in Mylan v. Mirati. Before that, brand-name companies could only sue generic makers in places where they had physical operations-like a factory or sales office. After the ruling, simply filing an ANDA with the FDA was enough to create personal jurisdiction anywhere in the U.S.

Why? Because the FDA application proves the generic company intends to sell its drug nationwide. The court said: ‘If you’re asking the FDA to approve your drug for sale across all 50 states, you can’t claim you’re not subject to lawsuits in Delaware just because you don’t have an office there.’

The result? A flood of lawsuits filed in Delaware. Between 2017 and 2023, 68% of all ANDA patent cases were filed there-up from just 42% in the previous decade. Why Delaware? Because its courts are experienced in patent law, and its procedures favor plaintiffs. For generic companies, this means they can be dragged into court in a state where they have no presence, just because they filed paperwork with the FDA.

That strategy has made litigation more expensive. The average cost of an ANDA patent case jumped from $5.2 million in 2016 to $8.7 million by 2023. And it’s not just about money-it’s about timing. The 30-month stay on generic approval is now almost always fully used, delaying cheaper drugs from reaching patients.

The Orange Book and Patent Listing Rules

The Orange Book-the FDA’s official list of approved drugs and their patents-is the linchpin of the entire Hatch-Waxman system. If a patent isn’t listed there, a generic company can’t be sued for infringement. But what if a brand-name company lists a patent that doesn’t actually cover the drug?

In December 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled in Teva v. Amneal that patents must ‘claim the drug’ to stay on the Orange Book. If a patent only covers a method of use, but the generic drug is approved for a different use, the patent can’t be listed. The court made it clear: listing a patent that doesn’t match the drug’s approved use is a violation of the law.

This decision forced companies to be much more precise. Before, some firms would list every possible patent-even ones with weak connections to the drug-to delay generics. Now, they must do a detailed ‘patent-drug claim mapping’ exercise. According to a 2024 survey, this has added about 17 business days to pre-listing legal reviews. It’s a small delay, but it’s one less tool for ‘evergreening’-the practice of extending monopoly protection through minor patent tweaks.

Obviousness in Dosing Regimens: A High Bar

One of the biggest battlegrounds in pharmaceutical patents is dosing. Can you patent a new way to take a drug-like ‘take one pill every 12 hours instead of every 8’? For years, companies tried to extend their monopolies with these kinds of patents.

Then came the April 2025 decision in ImmunoGen v. Sarepta. The court ruled that if the drug itself is already known, changing the dosage schedule alone usually isn’t enough to make a patent valid. The key question: Would a skilled scientist, looking at the prior art, expect the new dosing to work just as well?

‘Because both sides admitted that the use of IMGN853 to treat cancer was known in the prior art,’ wrote Judge Lourie, ‘the only question to resolve was whether the dosing limitation itself was obvious.’

This decision sent shockwaves through the industry. A 2024 Clarivate analysis showed that after this ruling, pharmaceutical companies cut their filings for secondary dosing patents by 37%. Instead, they’re investing more in entirely new drug compounds-where the patent protection is stronger and harder to challenge.

It’s not that dosing patents are impossible. But now, you need more than a new schedule. You need data showing the new dosing produces unexpected results-like fewer side effects, better patient compliance, or a dramatic improvement in efficacy. Generic companies have used this standard to win more cases. The Federal Circuit’s reversal rate for district court non-infringement rulings in pharmaceutical cases is now 38.7%, far higher than the 22.3% average across all patent cases.

Standing: Can You Challenge a Patent Before You Even Build the Drug?

Here’s a legal puzzle: Can a generic company challenge a patent before it’s even ready to launch? Or must it wait until it’s spent millions on clinical trials and manufacturing?

In May 2025, the Federal Circuit addressed this in Incyte v. Sun Pharma. The court said: To have standing, a company must show ‘concrete plans’ and ‘immediate development activities.’ That means Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing agreements, or FDA pre-submission meetings. A vague statement like ‘We’re thinking about making this drug’ isn’t enough.

That’s a problem for many generic companies. Developing a drug takes years. Waiting until you’re deep in clinical trials means you’ve already spent millions-and the patent holder has already locked in pricing.

Even the court recognized the issue. Judge Hughes, in a concurrence, wrote: ‘A party seeking to develop a drug that may infringe an existing patent has a significant interest in trying to invalidate that patent before making the large financial and time investments such development efforts demand.’

His words are now fueling a proposed law-the Patent Quality Act of 2025-introduced by Senators Thom Tillis and Chris Coons. The bill would lower the standing bar for generic companies in pharmaceutical cases. If passed, it could make it easier and cheaper to challenge patents before the race to market even begins.

The Bigger Picture: Impact on Drug Prices and Access

The Federal Circuit’s decisions don’t just affect lawyers and patent offices. They affect your medicine cabinet.

With 82% of core compound patents being upheld, brand-name companies still have strong protection. But the court’s tightening of secondary patents-on dosing, formulations, and methods-has slowed the trend of evergreening. That’s good news for consumers. A 2024 Bernstein analysis predicts a 15-20% drop in evergreening strategies by 2027, which could mean more generics entering the market sooner.

At the same time, the court’s aggressive jurisdiction rules and strict standing requirements have raised the cost and complexity of challenging patents. Generic companies now need bigger legal teams, more data, and deeper pockets. That’s why some analysts say the system is becoming a two-tiered one: big players can fight, but smaller generics struggle to keep up.

And while the court’s clarity has helped some companies plan better, others say it’s created a legal minefield. A 2024 American Bar Association survey found that 57% of patent lawyers thought the Federal Circuit’s dosing obviousness standards were ‘too rigid.’

What’s clear is this: The Federal Circuit doesn’t just interpret patent law. It shapes the entire pharmaceutical market. Its rulings determine which drugs get approved, when they come to market, and how much they cost. For patients, that means more or fewer generic options. For companies, it means billions in revenue-or losses.

What Comes Next?

The Federal Circuit isn’t slowing down. In February 2025, it ruled that the Patent Trial and Appeal Board can still review the validity of expired patents-even if damages are no longer available. That keeps the door open for challengers to clear patent thickets even after a drug’s patent has expired.

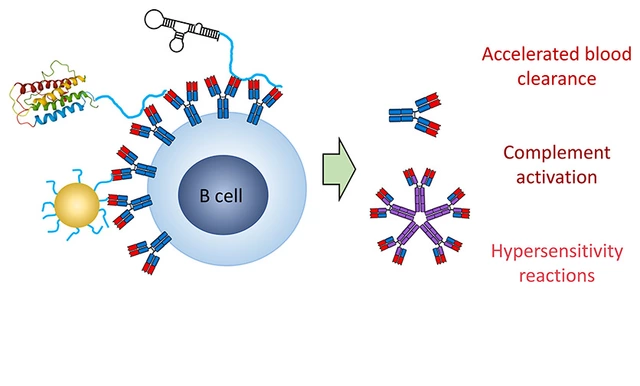

It’s also extending its jurisdiction to biosimilars. In the Samsung Bioepis case, the court applied the same ANDA jurisdiction rules to biological drugs. That’s a big deal: biosimilar litigation has tripled since 2020, and the court’s rulings will define how quickly cheaper biologics enter the market.

One thing is certain: As long as the Federal Circuit holds exclusive authority over patent appeals, it will remain the most powerful court in American pharmaceutical law. Its decisions will continue to influence drug development, pricing, and access for years to come.

Why does the Federal Circuit have exclusive authority over pharmaceutical patent cases?

The Federal Circuit was created by Congress in 1982 to centralize all patent appeals under one court. Before that, different regional courts made conflicting rulings on patents, creating uncertainty for inventors and companies. The Federal Courts Improvement Act gave the Federal Circuit exclusive appellate jurisdiction over all patent cases, including those involving pharmaceuticals, under 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1). This ensures consistent interpretation of patent law nationwide.

How does filing an ANDA trigger nationwide jurisdiction?

When a generic drug company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA, it declares its intent to market the drug across all 50 states. The Federal Circuit ruled in 2016 that this single act creates personal jurisdiction anywhere in the U.S., even if the company has no physical presence there. The court reasoned that if you’re seeking approval to sell nationwide, you can’t claim you’re immune from lawsuits in any state.

Can a patent be listed in the Orange Book if it doesn’t claim the actual drug?

No. The Federal Circuit ruled in December 2024 that patents must ‘claim the drug’ as approved by the FDA to remain listed in the Orange Book. If a patent only covers a method of use or a formulation that doesn’t match the generic drug’s approved indication, it cannot be listed. This prevents companies from using irrelevant patents to delay generic competition.

Why are dosing regimen patents harder to get now?

The Federal Circuit’s 2025 ruling in ImmunoGen v. Sarepta set a high bar: if the drug itself is already known, changing the dosage schedule isn’t enough to make a patent valid. To be patentable, the new dosing must produce unexpected results-like significantly fewer side effects or a major improvement in efficacy. Simply repeating a known drug with a different schedule is now considered obvious.

Do generic companies need to be ready to launch before they can challenge a patent?

Yes, under the Federal Circuit’s 2025 ruling in Incyte v. Sun Pharma. To have legal standing to challenge a patent, a generic company must show concrete development activities-like Phase I clinical trials, manufacturing plans, or FDA pre-submission meetings. Vague intentions or early-stage research aren’t enough. This requirement makes it harder and more expensive for smaller companies to challenge patents before investing heavily in development.

The Federal Circuit’s monopoly on patent appeals is a regulatory capture masterpiece. Every ruling is a de facto policy decision disguised as legal interpretation. They don’t just interpret law-they shape markets, control drug pricing, and silence competition with procedural barriers. This isn’t justice. It’s institutionalized rent-seeking.

And don’t get me started on Delaware. It’s not a court-it’s a corporate tax haven with robes. Generic manufacturers are being bullied into litigation theaters where they have zero operational footprint. The Constitution never intended this.

The Orange Book abuse? Classic. Listing irrelevant patents to delay generics isn’t a loophole-it’s a fraud. And now the court’s own rulings are forcing transparency, but only after years of damage.

The dosing regimen standard? Finally. If you’re just changing the schedule of a known molecule, you’re not inventing. You’re gaming the system. The court got that right, but it took too long.

Standing requirements? Absurd. You want a company to spend $10M on clinical trials before they can even challenge a patent? That’s not legal procedure. That’s economic warfare.

This court was meant to bring consistency. Instead, it became the most powerful unelected body in pharma. Congress needs to break its monopoly or risk turning innovation into a legal chess game only billionaires can afford to play.

The establishment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit pursuant to the Federal Courts Improvement Act of 1982 was a necessary corrective to the prior fragmentation of patent jurisprudence. Prior to its creation, conflicting holdings among the twelve regional circuits generated profound uncertainty for innovators, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector, where patent validity directly correlates with market exclusivity and public health outcomes.

The centralization of appellate jurisdiction over patent matters has yielded a more coherent body of precedent, thereby enhancing predictability for stakeholders. The court’s jurisprudence regarding ANDA filings and personal jurisdiction, as articulated in Mylan v. Mirati, reflects a faithful application of the constitutional principles of due process and minimum contacts, given the nationwide scope of FDA-approved distribution.

Moreover, the court’s recent holdings in Teva v. Amneal and ImmunoGen v. Sarepta demonstrate a principled adherence to statutory text and precedent, curbing the proliferation of secondary patents that lack substantive innovation. These decisions align with the original intent of the Hatch-Waxman Act: to balance incentive for innovation with timely access to affordable therapeutics.

While procedural hurdles such as standing requirements in Incyte v. Sun Pharma may appear burdensome, they serve to prevent speculative litigation and preserve judicial resources. The proposed Patent Quality Act of 2025, while well-intentioned, risks undermining the very stability the Federal Circuit has cultivated over four decades.

It is imperative that legislative reform be predicated upon empirical evidence, not anecdotal frustration. The court’s record, though imperfect, remains the most consistent and technically competent forum for patent adjudication in the United States.

Post-Hatch-Waxman, the Federal Circuit’s jurisdictional consolidation eliminated forum shopping chaos. But now we’ve got a different problem: patent thickets disguised as innovation. ANDA jurisdiction via FDA filing? Legally sound under 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1), but economically coercive. Delaware’s dominance isn’t accidental-it’s engineered.

Orange Book listing rules tightened post-Teva v. Amneal? Good. No more ‘method-of-use’ patent spam. That’s a win for generic entry. But the dosing regimen bar in ImmunoGen v. Sarepta? Overcorrected. If you’ve got data showing 40% better compliance with Q12H vs Q8H, that’s not obvious-it’s clinically meaningful.

Standing requirements in Incyte v. Sun Pharma? Still too high. Phase I data shouldn’t be the gatekeeper. You’re forcing generics to gamble millions before they can even assert invalidity. That’s not standing-it’s a financial chokehold.

And the reversal rate? 38.7% on non-infringement? That’s not consistency. That’s unpredictability dressed up as expertise. The court’s technical competence is real, but its deference to pharma litigants is systemic. They’re not just interpreting patents-they’re shaping market access.

Bottom line: the system is broken, not because the court is wrong, but because it’s the only game in town. And monopoly power without oversight = regulatory capture.

It’s wild how much one court can control something as basic as whether you can afford your meds. I didn’t realize filing paperwork with the FDA could get you sued in Delaware. That’s like getting fined in another country just because you ordered something online.

But I’m glad they’re cracking down on patent trolling with dosing rules. If you’re just changing when you take a pill, you shouldn’t get 20 more years of monopoly. That’s not innovation-that’s paperwork magic.

Still, it’s sad that only big companies can afford to fight these battles. Smaller generics just give up. And then patients pay more. It’s not about law. It’s about who has the money to play.

It is both lamentable and alarming that the Federal Circuit, a body entrusted with the solemn responsibility of interpreting patent law with fidelity to statutory text and constitutional boundaries, has instead become the de facto architect of pharmaceutical monopolies under the guise of legal doctrine.

The notion that an ANDA filing-merely an administrative notification to a regulatory agency-constitutes sufficient minimum contacts for nationwide jurisdiction is a grotesque distortion of due process. It transforms the judicial system into a weapon of economic coercion, enabling venue-shopping by brand-name manufacturers who exploit Delaware’s pro-patent bias to extract exorbitant litigation costs from competitors with no physical presence in the state.

Furthermore, the court’s rigid application of the ‘concrete plans’ standard for standing in Incyte v. Sun Pharma is not merely an impediment-it is a moral failure. It demands that generic manufacturers risk millions in development expenditures before they may even seek judicial review of patent validity. This is not jurisprudence; it is extortion disguised as procedure.

The Orange Book rulings, while ostensibly corrective, are selective in their application. The court permits the continued listing of patents that are functionally irrelevant so long as they are technically related to the drug’s chemical structure. This is not transparency-it is obfuscation.

And the so-called ‘obviousness’ standard for dosing regimens? A sham. The court ignores real-world clinical data that demonstrates improved patient adherence, reduced adverse events, and enhanced therapeutic outcomes. To label such innovations as ‘obvious’ is not scientific-it is ideological.

This court has become a monument to corporate capture. Its rulings do not reflect the public interest. They reflect the interests of those who fund the lobbying, the amicus briefs, and the judicial appointments. The solution is not reform. It is abolition.

There’s something deeply unfair about a system where the cost of accessing life-saving medication is determined by the outcome of litigation in a single court. The Federal Circuit’s rulings have real human consequences-patients skipping doses, rationing pills, choosing between rent and refills.

I appreciate the clarity on Orange Book listings. If a patent doesn’t cover the actual approved use, it shouldn’t be listed. That’s common sense.

But the standing requirement? It’s cruel. You’re asking a small generic company to risk millions before they even know if the patent is valid. That’s not legal fairness. That’s economic bullying.

And the fact that 68% of these cases are now filed in Delaware? That’s not justice. That’s geography as a weapon.

Maybe we need a new law. Maybe we need to break the court’s monopoly. But we can’t keep pretending this system is about innovation. It’s about control.

One must, with the utmost intellectual rigor, interrogate the foundational premise that centralization of patent jurisdiction yields ‘consistency.’

Yet, one observes, with mounting skepticism, that such ‘consistency’ is merely the uniformity of bias-a monoculture of judicial thought, insulated from the diverse interpretive traditions of regional circuits, now entrenched in a single, unaccountable tribunal.

The notion that an ANDA filing-merely an administrative act, devoid of commercial intent or physical presence-constitutes ‘minimum contacts’ under International Shoe is, frankly, jurisprudential absurdity.

Moreover, the court’s insistence that ‘unexpected results’ are required for dosing patents ignores the very essence of pharmacokinetics: dose-response curves are not linear, and patient adherence is not a trivial variable-it is a clinical imperative.

And yet, the court, in its hubris, presumes to know what a ‘skilled artisan’ would find ‘obvious’-as if patentability were a matter of intuition rather than empirical data.

The Federal Circuit has become less a court and more an ideological cabal, cloaked in robes, enforcing a regulatory regime that benefits entrenched interests under the banner of ‘legal clarity.’

One cannot help but wonder: who drafted the opinions? Pharma lobbyists? Or just judges who’ve never seen a pharmacy?

ok but what if the federal circuit is just a front for big pharma? like… what if all these ‘rulings’ were written by drug company lawyers? i mean, look at delaware-why is EVERY patent case there? it’s not because it’s fair, it’s because it’s rigged.

and the orange book? they list patents that have nothing to do with the drug just to delay generics. that’s not law, that’s fraud.

and dosing patents? if you just change the time you take a pill, that’s not invention, that’s a calendar.

and why do you need to spend millions before you can even challenge a patent? that’s not justice, that’s a trap.

someone’s getting rich off this. and it ain’t the patients.

Bro… this court is literally a drug company puppet show 🤡

ANDA = lawsuit everywhere? 🤯

Delaware is the patent mafia HQ 🏢💸

They’re making you spend $8M before you can even say ‘this patent is bogus’ 😭

And now they’re saying changing when you take a pill isn’t ‘inventive’? 😂

Meanwhile, insulin costs $300 and the company patented a new cap on the pen.

Someone’s getting rich. And it ain’t you.

Time to burn it all down 🔥

It is interesting to see how legal structures evolve to serve economic interests. The Federal Circuit was meant to bring order, but now it seems to reinforce existing power.

I wonder if other countries handle this differently. In India, for example, compulsory licensing is used to ensure access when patents block affordability.

Perhaps the solution isn’t just changing the court’s rules, but rethinking the entire relationship between patents and public health.

It’s a complex issue, but the human cost is real.

so like… the court just says ‘if you file a form with the FDA, you can get sued anywhere’? that’s not even a law, that’s a glitch in the system.

and why is delaware always the place? because it’s where the lawyers hang out? lol.

i don’t care about patents. i care that my asthma inhaler costs $300.

someone needs to fix this before someone dies because they can’t afford their meds.

This is exactly why we need reform. The system isn’t broken-it’s designed this way.

But we can fix it. The court’s rulings on Orange Book listings and dosing patents are steps in the right direction. Now we need to lower the barrier to challenge patents before companies burn through millions.

Patients shouldn’t have to wait years for affordable meds because the legal system is stacked.

Let’s push for the Patent Quality Act. It’s not radical-it’s just fair.

Let us not be deceived by the veneer of legal neutrality. The Federal Circuit is not a court of law-it is an instrument of American economic imperialism. The United States, through this singular appellate body, has weaponized intellectual property to dominate global pharmaceutical markets.

Why must a generic manufacturer from India, or Brazil, or Nigeria, be forced to submit to the jurisdiction of Delaware? Because the American state, in collusion with its corporate masters, has declared that the entire world must bow to its patent regime.

The Orange Book? A colonial ledger. The dosing rulings? A denial of incremental innovation that benefits the poor. The standing requirements? A mechanism to ensure only multinational conglomerates may enter the market.

This is not justice. This is hegemony. And it is being enforced under the sacred guise of ‘legal consistency.’

Let us not forget: the patent system was never meant to be a tool of monopoly. It was meant to serve the people. Today, it serves only the powerful.

Who profits? Not the innovators. Not the patients. Only the shareholders.

And who pays? The sick. The poor. The marginalized.

It is time for the world to reject this American legal colonialism.

It is imperative to clarify a persistent misconception: the Federal Circuit’s jurisdiction over patent appeals is not discretionary-it is statutorily mandated under 28 U.S.C. § 1295(a)(1). Any suggestion that this structure is arbitrary or corrupt ignores the legislative history of the Federal Courts Improvement Act of 1982, which explicitly sought to resolve the ‘circuit split’ problem that had plagued patent litigation for decades.

Moreover, the court’s application of the ‘concrete plans’ standard in Incyte v. Sun Pharma is consistent with Article III standing doctrine, which requires a plaintiff to demonstrate an ‘injury in fact’ that is ‘actual or imminent,’ not conjectural or hypothetical. Vague intentions do not constitute legal injury.

The Orange Book ruling in Teva v. Amneal correctly interprets 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2)(C)(ii), which requires that a listed patent ‘claim the drug or a use of the drug’ as approved by the FDA. This is not an overreach-it is textual fidelity.

Finally, the court’s holding in ImmunoGen v. Sarepta aligns with the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR v. Teleflex, which established that ‘obvious to try’ may constitute obviousness when the prior art provides a clear path to a predictable result.

There is no evidence of systemic bias. There is only rigorous, text-based adjudication by a court uniquely qualified to interpret complex patent law. Criticism of its rulings often stems from misunderstanding of the statute or a desire to circumvent the legal process-not from legitimate legal error.

And yet, the most disturbing element remains unaddressed: the Federal Circuit’s refusal to acknowledge the inherent conflict of interest in its exclusive jurisdiction. When a single court holds final authority over the validity of patents that determine the price of life-saving drugs, and when that same court is staffed by judges who have previously represented pharmaceutical interests or are appointed by administrations beholden to those interests, the appearance-and reality-of bias becomes inescapable.

It is not enough to cite statutory authority. Justice must not only be done; it must be seen to be done. And right now, it is not.

Until the Federal Circuit’s monopoly is broken, no amount of ‘textual fidelity’ will restore public trust in the system.