Cerebral Palsy is a neurological disorder that affects movement, posture, and muscle tone, originating from brain injury before, during, or shortly after birth. Receiving a diagnosis can feel overwhelming, but a clear plan-combining medical care, therapy, technology, and emotional support-turns uncertainty into action.

Why a Structured Plan Matters

Research from leading pediatric centers shows that early, coordinated intervention improves functional outcomes by up to 30%. The brain’s plasticity is highest in the first few years, so turning the diagnosis into a roadmap helps the child reach developmental milestones faster and eases family stress.

Step1: Assemble the Core Care Team

The first job is to surround yourself with specialists who understand the spectrum of cerebral palsy. Key members include:

- Pediatric Neurologist - coordinates medical evaluation, orders imaging, and monitors neurological progression.

- Physical Therapist - designs exercises that improve strength, balance, and gait.

- Occupational Therapist - focuses on fine motor skills, daily living activities, and adaptive equipment.

- Speech‑Language Pathologist - addresses speech, swallowing, and communication devices.

- Mental Health Counselor - offers coping strategies for the child and family.

- Assistive‑Technology Specialist - matches the child with devices like wheelchairs, communication apps, or orthotics.

Schedule a multidisciplinary meeting within the first month after diagnosis. Ask each professional for a written summary of recommendations; this becomes the backbone of your management plan.

Step2: Choose the Right Therapies

Therapy selection hinges on the child’s type of cerebral palsy (spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, or mixed) and functional goals. Below is a side‑by‑side look at the three core therapy streams.

| Therapy | Primary Focus | Typical Sessions per Week | Main Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Therapy | Mobility, strength, balance | 2-4 | Improve walking ability or safe transfers |

| Occupational Therapy | Fine motor, ADL independence | 2-3 | Enable self‑feeding, dressing, and classroom tasks |

| Speech‑Language Pathology | Communication, feeding, oral motor | 1-2 | Clear speech or effective AAC use; safe swallowing |

Tip: Track progress with a simple spreadsheet-note dates, exercises, and observed improvements. Sharing this data with the care team keeps everyone aligned.

Step3: Integrate Assistive Technology Early

Assistive devices bridge the gap between ability and environment. Common options include:

- Mobility aids: custom‑fit wheelchairs, gait trainers, or ankle‑foot orthoses that support walking.

- Communication tools: speech‑generating apps (e.g., Proloquo2Go) or eye‑tracking systems for non‑verbal children.

- Environmental controls: switch‑activated lights, smart home hubs, and adapted keyboards for school work.

Research from the National Center for Assistive Technology indicates that early device adoption can raise participation scores by 20‑25% in school settings. Work with the Assistive‑Technology Specialist to trial devices before purchase; many programs offer loan periods.

Step4: Build a Support Network

Emotional resilience stems from connection. Two pillars are essential:

- Support Groups - local or online communities where families share resources, celebrate milestones, and vent frustrations.

- Parent Education Programs - workshops that teach positioning, home exercise routines, and advocacy skills.

Statistics from the Cerebral Palsy Alliance show that parents who attend regular group meetings report 40% lower stress scores. Look for groups hosted by hospitals, NGOs, or national CP registries.

Step5: Prioritize Mental Health for the Whole Family

Living with CP can trigger anxiety, depression, or grief. A dedicated Mental Health Counselor can:

- Teach coping strategies (mindfulness, CBT techniques).

- Facilitate family therapy to improve communication.

- Help the child develop self‑advocacy skills appropriate to age.

Evidence‑based programs like “Families Living With CP” report measurable improvements in quality‑of‑life scores after eight weekly sessions.

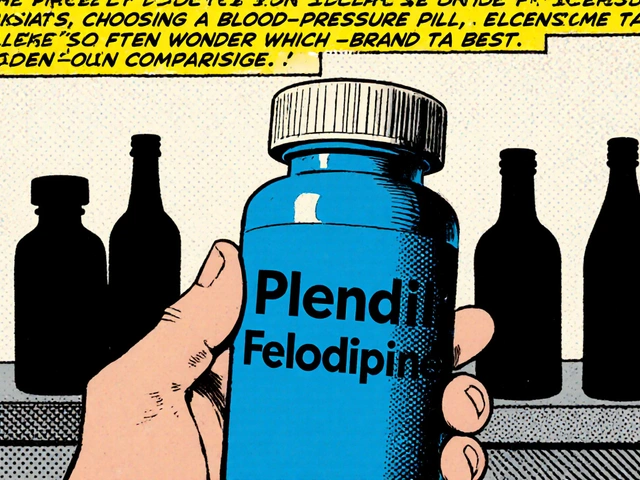

Step6: Manage Medications Wisely

While therapy is the cornerstone, medications may address spasticity, seizures, or pain. Common categories include:

- Antispasmodics (e.g., baclofen, diazepam)

- Botulinum toxin injections for focal muscle tightness

- Anticonvulsants if seizures are present

- Analgesics for joint discomfort

Maintain a medication log-dose, timing, side effects-and review it with the pediatric neurologist every three months. Adjustments are often needed as the child grows.

Step7: Plan for School and Community Inclusion

Early collaboration with educators ensures the child receives necessary accommodations. Key actions:

- Request an Individualized Education Program (IEP) that lists therapy minutes, assistive devices, and transition supports.

- Identify a school‑based therapist (often OT or PT) to continue goals during the day.

- Educate peers through classroom talks; inclusion improves social outcomes.

Data from the US Department of Education shows that students with CP who have a well‑implemented IEP graduate high school at rates 15% higher than peers without an IEP.

Step8: Review and Adjust the Plan Regularly

Every six months, sit down with the core team and ask:

- What goals have been met?

- Are there new challenges (e.g., puberty, changing mobility needs)?

- Do we need additional services (e.g., neuropsychology, transition planning for adulthood)?

Flexibility is key; as the child ages, therapy frequency, device needs, and medical considerations evolve.

Key Takeaways

Managing a cerebral palsy diagnosis isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all checklist; it’s a living system of medical care, therapy, technology, and emotional support. By building a multidisciplinary team, choosing evidence‑based therapies, embracing assistive tech, and fostering community ties, families can transform a daunting diagnosis into a roadmap for growth and independence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best age to start physical therapy for a child with cerebral palsy?

Early intervention yields the biggest gains. Most specialists recommend beginning PT as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, often within the first 6‑12 months of life. The brain’s plasticity enables faster motor skill acquisition during this window.

How can I tell if my child needs an orthotic device?

Common signs include persistent toe‑walking, uneven leg lengths, or difficulty standing with knees straight. A pediatric orthotist will conduct a gait analysis and recommend a custom‑fit brace if needed.

Are there financial assistance programs for assistive technology?

Yes. Many state Medicaid plans cover durable medical equipment. Non‑profits like United Cerebral Palsy and local CP foundations also offer grants or loan programs for devices such as wheelchairs and communication apps.

What mental‑health resources are most helpful for parents?

Parent‑focused counseling, peer‑support groups, and respite‑care services reduce burnout. Cognitive‑behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness‑based stress reduction have proven effective in clinical trials.

How often should the care plan be reviewed?

A six‑month review is a good rule of thumb, but adjustments may be needed sooner if there are changes in mobility, school demands, or health status.

Can children with cerebral palsy lead independent adult lives?

Absolutely. With a robust support system, appropriate therapies, and assistive technology, many adults with CP attend college, hold jobs, and live semi‑independently. Transition planning should begin in early teens to set academic and vocational goals.

Wow, because a checklist magically fixes everything.

I feel like every parent is thrown into a storm of medical jargon and endless meetings. The guide tries to be a lighthouse, but the waves keep crashing. It’s heartbreaking to see families scramble for answers while feeling isolated. The emotional roller‑coaster is real and raw. Still, having a roadmap can calm the chaos, even if just a little. The steps feel like a lifeline stretched across a void. My heart goes out to anyone navigating this maze. Remember, you are not alone in this fight.

Don't be fooled, the so‑called “multidisciplinary team” is often a front for hidden insurance agendas. Behind the polite smiles lies a profit machine that decides who gets what equipment. Every recommendation is filtered through a bureaucratic maze designed to drain resources. It's a puppet show, and the child is the unwitting marionette. Trust no one until you have the paperwork in hand, and even then, stay vigilant.

When we conceptualize cerebral palsy management as a dynamic systems model, we foreground the interplay between neuroplastic adaptation and environmental affordances, thereby transcending a static checklist paradigm. The literature underscores that early, intensive motor learning protocols, calibrated to the individual's motor schemas, catalyze synaptic reorganization, particularly within the corticospinal tract. Concurrently, the integration of assistive technology functions as a scaffold, extending the functional reach of the child while attenuating compensatory maladaptations. One must therefore orchestrate a synchronized regimen wherein physical, occupational, and speech‑language interventions are temporally interleaved, maximizing dosage without precipitating fatigue. In practice, this equates to structuring bi‑weekly PT blocks flanked by OT sessions that emphasize fine motor dexterity, with SLT embedded on alternate days to reinforce phonatory precision. The role of neuropharmacology, although ancillary, cannot be ignored; judicious titration of antispasmodics facilitates smoother motor execution during therapeutic windows. Moreover, caregiver-mediated home programs augment clinic‑based therapy, fostering a continuum of care that respects the principle of use‑dependent plasticity. Data from longitudinal cohort analyses reveal that families who maintain a digital log of milestones exhibit a 22% higher rate of goal attainment, a statistic that speaks to the power of feedback loops. It is imperative to embed iterative outcome measures-such as the GMFM‑66 and PEDI-within the care plan, enabling real‑time recalibration of objectives. Ethical considerations also surface; informed consent must encompass discussions about the potential psychosocial impact of early device implantation. Finally, transitioning to adolescent and adult services requires preemptive planning, aligning vocational training with adaptive equipment to ensure continuity of independence. In sum, a holistic, evidence‑informed schema that harmonizes neurophysiological principles with pragmatic support systems offers the most robust pathway toward functional optimization. Future research should explore the synergistic effects of virtual reality‑based motor training combined with biofeedback mechanisms, as early pilot studies suggest enhanced cortical activation patterns. Additionally, policy advocacy to streamline Medicaid coverage for emerging technologies can alleviate financial barriers that often impede equitable access. Collaboration across multidisciplinary teams and community stakeholders creates a resilient ecosystem capable of adapting to the evolving needs of the child. Ultimately, the convergence of scientific rigor, compassionate care, and systemic support transforms a daunting diagnosis into a catalyst for growth.

This so‑called “holistic” approach is nothing but academic fluff designed to justify endless paperwork. Parents need clear, actionable steps, not a dissertation on neurophysiology. Cut the jargon and give us the damn schedule now.

Hey everyone, I just wanted to throw some positive vibes into the mix! Seeing all these detailed strategies reminds me why community support is the secret sauce that makes everything work. When you combine professional guidance with a tight‑knit network of parents, siblings, and friends, the whole system becomes far more resilient. I’ve watched families rally around each other, swapping tips about the best wheelchair models, sharing favorite therapy games, and even organizing car‑pool trips to appointments. Those small acts of solidarity can dramatically reduce stress levels and boost motivation for both the child and the caregivers. So keep the momentum going, celebrate each tiny victory, and remember that every laugh, every high‑five, and every shared resource counts. Together, we can turn challenges into triumphs, one step at a time.

While the presented guide is comprehensive, its utility may be limited for families lacking immediate access to multidisciplinary resources. A more nuanced discussion of socioeconomic disparities would enhance its relevance.

Yo, love the vibes in the thread! Just a heads up-if u’re hunting for cool apps, check out “TalkTablet” and “WheelMe” – they’re pretty rad and actually user‑friendly. Also, don’t forget the power of emojis 😂-they can lighten the mood when things get heavy.

✅ Absolutely! Let’s keep sharing the love and resources 💪😊